Shakespeare’s “creative spellings” gave us these 10 words we still can’t live without

[ad_1]

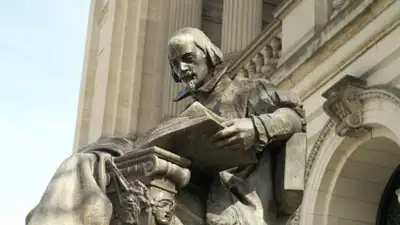

William Shakespeare, born in 16th-century Stratford-upon-Avon, England, didn’t simply use language as a tool to tell tales, he wielded it like a master craftsman, shaping it to fit his vision. In fact, his name appears in various spellings across historical records, each reflecting the fluidity of language during that time. The English language in the 16th century wasn’t standardised like it is today. People often wrote as they spoke, and spelling was a matter of personal choice. For an ordinary student struggling to get their English spelling right, it was a remarkable time to be alive. Or, if you were a wordsmith like Shakespeare, it offered endless possibilities to bend and meld words into unique contexts and usages.Shakespeare was no ordinary writer, his plays have shaped English literature, and so have his words. Even centuries after his death, they remain indispensable to the English language. Imagine what it would be like today if students were free to play with language in the way Shakespeare did. In modern classrooms, a paper full of such “creative spelling” would likely be defaced with red ink. Yet, what might be deemed ‘creative spellings’ or even ‘mistakes’ in a modern classroom, are precisely what have left a lasting legacy, one that both students and linguists continue to rever.

1. Eyeball (Henry VI, Part 1)

Believe it or not, the word “eyeball” was Shakespeare’s invention. Before his time, people simply used “eye,” but he introduced “eyeball” to specifically describe the spherical structure of the eye. Was this intentional word-smithing or merely a quirky choice in the heat of dramatic expression? Perhaps both, but the result was a word we simply cannot imagine living without today.

2. Bedroom (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

Imagine a world without the word “bedroom.” Shakespeare combined the straightforward words “bed” and “room” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream to give us the term we now use to describe our most personal space. Whether this was a grammatical “mistake” or an act of linguistic invention, this creative leap has certainly stood the test of time.

3. Swagger (Henry V, A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

Shakespeare didn’t just write about kings and battles, he gave us an attitude. In Henry V, he coined “swagger”, a word originally describing an arrogant strut. Today, it’s evolved into a term for effortless confidence. Was it a playful jab at bravado or a stroke of linguistic genius? Either way, Shakespeare’s “swagger” has strutted its way into modern slang.

4. Dwindle (Henry IV, Part 1, Macbeth)

Why use a plain word when Shakespeare could shrink it into something new? In Macbeth, he conjured “dwindle”, a poetic verb for slowly fading away. Did he mishear an older term, or was this a sly contraction? Whatever the case, this haunting word has dwindled its way into everyday speech.

5. Jaded (Henry VI, Part 2)

“Jaded”, that feeling of being thoroughly worn out or exhausted, first appeared in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2. In this instance, Shakespeare didn’t “misspell” anything; he introduced a fresh way of describing fatigue. By blending words and meaning, Shakespeare created a term that perfectly captured the weary, worn-out feeling we still experience today.

6. Green-Eyed (The Merchant of Venice, Othello)

Shakespeare loved vivid imagery, and few phrases stick like “green-eyed monster” (jealousy) from Othello. While “green-eyed” itself wasn’t entirely new, his dramatic personification turned it into a timeless expression. A playful twist on color and emotion? Absolutely. A “mistake”? Hardly, just another example of Shakespeare painting with words.

7. Bedazzled (The Taming of the Shrew)

Shakespeare possessed an incredible ability to conjure vivid, eye-catching imagery with his words. In The Taming of the Shrew, he coined “bedazzled”, a word meaning to impress someone with overwhelming beauty or brilliance. What may have seemed like a playful misstep in his writing led to a dazzling, enduring term.

8. Sanctimonious (The Tempest)

Who doesn’t know a sanctimonious person, someone who presents themselves as morally superior, often in a rather hypocritical way? Shakespeare gave us this word in The Tempest. Was it a “spelling mistake,” or was it an inspired bit of wordplay that added layers of irony to his characterisations? In any case, the term became essential for describing pretentious piety, and it’s now commonplace in our vocabulary.

9. Grovel (Henry VI, Part II)

To “grovel” means to lower oneself in humility or submission. Shakespeare employed this term in Henry VI, Part II, and it quickly caught on as a way to describe extreme humility. Whether it was a slip of the pen or deliberate wordplay, “grovel” remains in the language as a perfect descriptor of humbling oneself to an exaggerated degree.

10. Gloomy (Titus Andronicus)

When Shakespeare used ‘gloomy’ in Titus Andronicus, he coined a term that would encapsulate dark moods and weather for centuries to come. His play was filled with tragedy and dark themes, and ‘gloomy’ perfectly captured that atmosphere. This evocative coinage gave us an indispensable way to describe emotional despair and dreariness.

A legacy, an idol, a sea of language awaiting words to come alive

If Shakespeare’s legacy outshines that of many of his contemporaries, it is well deserved. The way he seized the opportunity to blend artistry with language gave him the freedom to invent words that the existing vocabulary simply couldn’t hold. Shakespeare didn’t just command language as if it were his own; he reshaped it forever, leaving behind a linguistic legacy for generations to come.So, next time you’re at a loss for words, why not channel the lost spirit of Shakespeare? Embrace your creativity, let language be what it was always meant to be: a tool for creation, communication, persuasion, and making an impact that, like Shakespeare’s, endures.

[ad_2]

Source link