IndiGo’s disruption as a lens on India’s transmission challenge

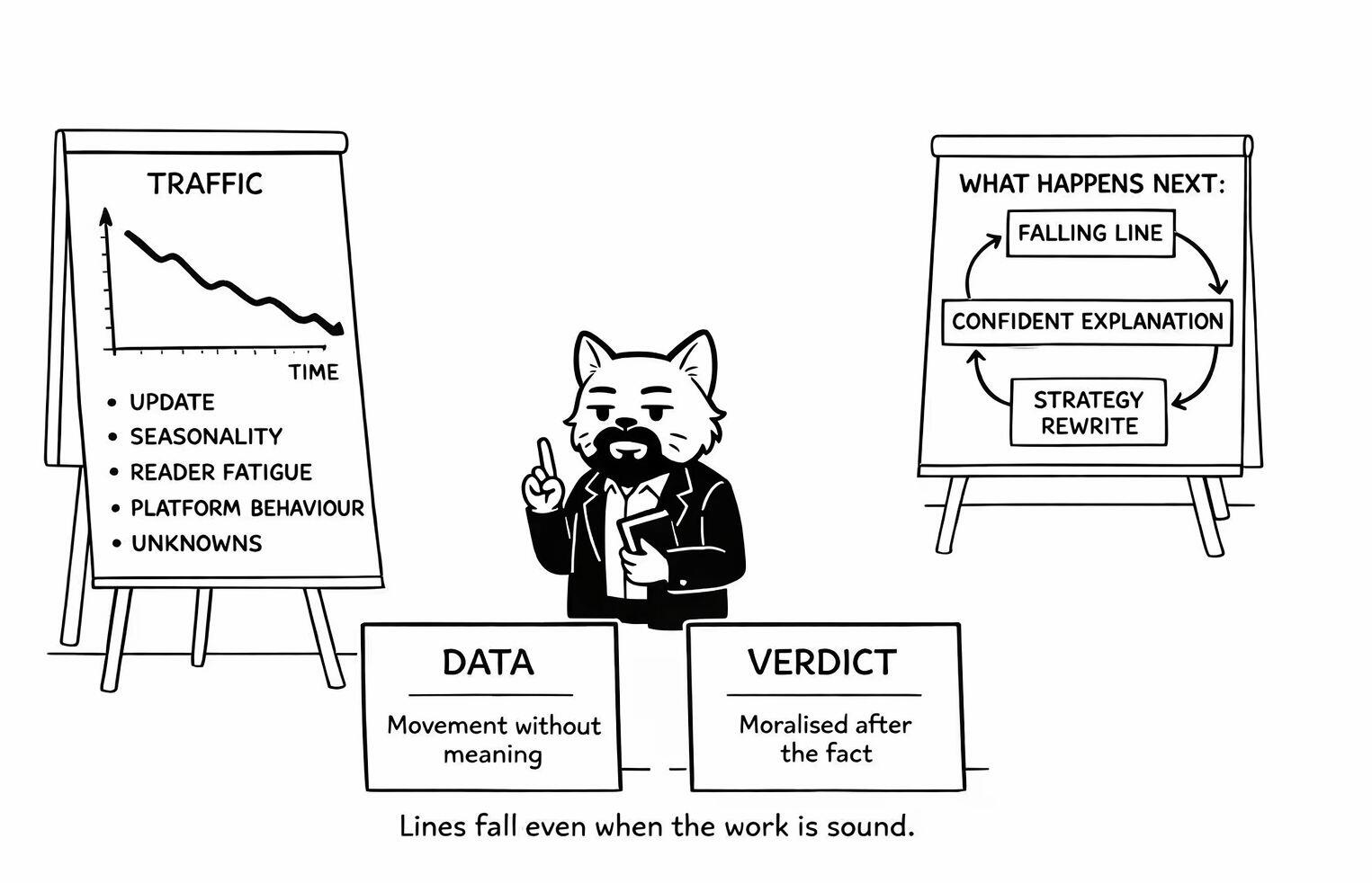

In early December 2025, IndiGo, the country’s largest domestic aviation carrier with more than 60% of the market, faced a crew-rostering and compliance shock. The immediate results were visible: flight cancellations multiplied across metros and smaller cities, delays spread through airport networks, and the DGCA was compelled to cut IndiGo’s winter programme to restore operational stability. Public attention, amplified by television and social media, understandably focused on passengers’ plight, inconvenience and anger. Yet we missed the deeper message here: when one firm carries such a large share of a network, its internal disruptions do not stay confined to the firm. It becomes a nationwide disruption because there are too few credible alternatives that can absorb the load at short notice. That is the essence of concentration risk in networked sectors.

There is a nuance of industries functioning like interconnected grids: reliability depends not just on each player performing, but on having enough spare capacity if one falters. When the dominant provider slips, others cannot take up the load fast enough, and the disruption spreads. At that scale, regulators are pushed from routine oversight into crisis management, resetting schedules, issuing stop-gap directions, and making temporary relaxations because stabilising the system becomes the top priority.

Power transmission in India is a network of this kind, even if it is less visible than aviation. It is the interstate framework that carries electricity across regions, translating generation into usable supply. Over the past decade, clean capacity has multiplied several times, placing India among the fastest-scaling renewable markets in the world. The national plan now is to ensure that transmission pathways keep pace with this growth.

However, in the past few years, we have witnessed a troubling pattern in how these projects are being awarded and executed. Interstate transmission development was opened to competitive bidding to allow both public and private firms to participate. The intention was to combine the scale and reliability of a national utility with the speed, technology adoption, and capital access that private developers can offer. In practice, however, awards have been clustering heavily with a single institution, Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd (PGCIL). Again, the issue is concentration and whether any sector benefits from having so much of its future dependent on one executor’s bandwidth, who becomes dominant.

The reasons behind this concentration are largely structural, i.e., the bidding model is anchored almost entirely on the lowest tariff, and PGCIL’s sovereign backing gives it a financing edge that private developers cannot reasonably match. Predictably, repeated losses thin the private bidding field, and the pipeline accumulates with one winner. The consequence is visible in slower grid development, delayed renewable evacuation corridors, and clean power being held back for want of timely connectivity. The IndiGo incident revealed this fragility starkly; with limited fallback capacity in the market, passengers had nowhere else to go, and the shockwaves travelled through the entire aviation system, leaving regulators in rapid damage control mode because alternatives are too thin.

In transmission, the equivalent outcome is stranded generation and firm-level right-of-way delays, contractor limits, procurement slippages, or supply-chain constraints that start governing national renewable timelines.

Losses and compensation petitions from transmission developers are early signals of this stress and signal to investors that evacuation risk is rising. The aviation parallel is instructive here, too, as IndiGo’s pricing efficiency helped expand access, but its dominance also meant that when it faltered, the entire market absorbed the cost of disruption. This is precisely why policy must lean toward resilience, not just scale.

India already uses practical guardrails against market concentration in other regulated sectors. Transmission can adopt a similar approach through a simple market-share cap on under-construction interstate projects. A 50% ceiling on the under-construction pipeline with any single developer would preserve the leading developer’s role while ensuring that unfinished work is not piled onto one portfolio at the same time. If a developer crosses the threshold, it continues executing existing projects but pauses from new awards until its share naturally falls. This spreads execution load, keeps multiple capable firms in the field, and reduces the chance that one portfolio’s slippage slows the entire clean-energy timetable. The mismatch between generation and transmission results in occasional “curtailment”, resulting in wastage of generation capacity and losses to the developers. Besides, it also affects investment attractiveness and the sentiments of new developers.

We require a grid that is not only large but also balanced in how it is built. IndiGo’s December disruption was a reminder of what over-dependence looks like in a networked service. The transmission lines are too central to the national future and development to run the same risk.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE