The algorithm enters classrooms: AI deepfakes and the fragile safety net around US students

Every school crisis tends to announce itself loudly. There are assemblies, letters home, emergency meetings and policy revisions drafted under pressure. But some of the most disruptive changes in education arrive without alarms. They enter quietly and reveal themselves only when harm has already been done.American schools are now confronting one such shift. Artificial intelligence, once discussed in classrooms as a future skill or ethical dilemma, is being used by students to generate sexually explicit deepfakes of their classmates. What begins as a few altered images can escalate into lasting trauma, legal consequences and institutional failure, exposing how unprepared schools remain for a form of harm that moves faster than rules, safeguards or adult awareness.

When harm arrives before systems do

The scale of the problem became visible this autumn in a middle school in Louisiana, where artificial intelligence–generated nude images of female students circulated among peers, the Associated Press reports. Two boys were later charged. But before accountability arrived, one of the victims was expelled after getting into a fight with a student she accused of creating the images. The sequence of events mattered as much as the crime itself: punishment landed faster on a harmed child than on those responsible for the harm.Law enforcement officials acknowledged how the technology has lowered the barrier to abuse. The ability to manipulate images is not new, but generative artificial intelligence has made it widely accessible, requiring little technical knowledge. The Louisiana case, reported by AP, has since become a reference point for schools and lawmakers trying to understand what has changed and why existing responses fall short.

A form of bullying that does not fade

What distinguishes AI-generated deepfakes from earlier forms of school bullying is not only their realism, but their persistence. A rumour fades. A message can be deleted. A convincing image, once shared, can resurface indefinitely. Victims are left not only defending their reputation, but their reality.The numbers suggest the problem extends far beyond isolated incidents. According to data citedf rom the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, reports of AI–generated child sexual abuse material surged from 4,700 in 2023 to 440,000 in just the first six months of 2025. The increase reflects both the spread of the technology and how easily it can be misused by people with no specialist training.

Laws catch up, unevenly

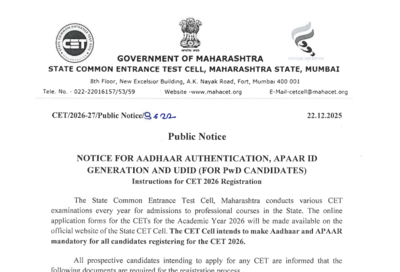

As the tools become simpler, the age of users drops. Middle school students now have access to applications that can produce realistic fake images in minutes. The technology has moved faster than the systems designed to regulate behaviour, assign responsibility or offer protection.Lawmakers have begun to respond, though unevenly. In 2025, at least half of US states enacted legislation aimed at deepfakes, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, with some laws addressing simulated child sexual abuse material. Louisiana’s prosecution is believed to be the first under its new statute, a point noted by its author in comments reported by AP. Other cases have emerged in Florida, Pennsylvania, California and Texas, involving both students and adults.

Schools left to improvise

Yet legislation alone does not determine how harm is handled day to day. That responsibility still falls largely on schools, many of which lack clear policies, training or communication strategies around AI-generated abuse. Experts interviewed by AP warn that this gap creates a dangerous illusion for students: that adults either do not understand what is happening or are unwilling to intervene.In practice, schools often respond using frameworks designed for earlier forms of misconduct. Discipline codes written for harassment, phone misuse or bullying struggle to account for an image that looks real, spreads quickly and causes harm without physical contact. Administrators are left balancing student safety, due process and reputational risk, often while learning about the technology in real time.

The weight carried by victims

The emotional impact on victims is severe. Researchers found that students targeted by deepfakes frequently experience anxiety, withdrawal and depression. The harm is compounded by disbelief. When an image appears authentic, denial becomes harder, even for peers who know it is fabricated. Victims may feel unable to prove what did not happen, while still living with the consequences of what others think they see.Parents are often drawn into the crisis after the damage has already spread. Many assume schools are monitoring digital behaviour more closely than they are. Others hesitate to intervene, unsure how to discuss AI without normalising its misuse. Some children, fearing punishment or loss of access to devices, remain silent.

Patchwork responses, fragile protection

Organisations working with schools have begun promoting structured responses. One widely shared framework encourages students to stop the spread, seek trusted adults, report content, preserve evidence without redistributing it, limit online exposure and direct victims to support. The length of the process itself reflects the complexity of the problem. Managing harm now requires technical awareness, emotional care and legal caution, often from families and schools with limited resources.What is missing, is a coherent safety net. Responsibility is fragmented across schools, parents, platforms and lawmakers. Technology companies rarely feature in school-level responses, even as their tools enable the abuse. Schools carry the burden of response without control over the systems that generate or distribute the content.

Watching where the cracks widen

As with many education crises, the effects will not be evenly distributed. Students with supportive families, legal resources or schools equipped to respond may find protection. Others will encounter delays, disbelief or punishment for reacting to harm. The risk is that AI deepfakes become another pressure point where existing inequalities shape outcomes.For now, there is no single fix. But there are signals worth watching. Whether schools update conduct policies to explicitly address AI misuse. Whether staff receive training that keeps pace with technology. Whether victims are supported before discipline is imposed. And whether responsibility begins to shift upstream, towards the platforms and systems that make such abuse possible.The algorithm has already entered classrooms. What remains uncertain is whether the institutions meant to protect students will adapt quickly enough, or whether, once again, children will be left carrying the cost of a transformation adults failed to anticipate.