Who guards the school gate? The stray-dog row that put teachers on the hook; here’s why they’re pushing back

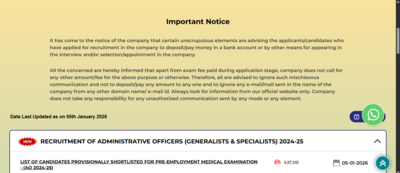

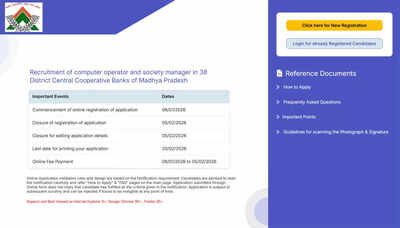

It began, like most modern education controversies do, with a court order meant to protect children—and ended with teachers being told (online) that they had been asked to do something they were never officially asked to do. On November 7, 2025, the Supreme Court, hearing Suo Motu WP(C) No. 5/2025 (“City Hounded by Strays, Kids Pay Price”), issued time-bound directions to secure institutional premises—schools, hospitals, sports complexes, bus depots and railway stations—from stray dog risks, and sought compliance from States/UTs. The administrative chain moved fast: A Ministry of Education (Department of Higher Education) letter asked educational institutions to appoint a nodal officer to coordinate upkeep, campus safety and municipal linkage, and to run awareness and first-aid preparedness. CBSE followed with a circular advising affiliated schools on preventing dog-bite incidents and managing strays in school premises.

Delhi then added its implementation layer: A DoE Caretaking Branch circular dated December 5 sought nomination/details of nodal officers for coordination—triggering teacher bodies’ objections over non-teaching duties.And then came the real accelerant: Social media posts recast “nodal officer” paperwork into the headline-friendly fiction of “teachers counting stray dogs”, which the DoE called misinformation prompting police/cyber-cell action.In the middle of all these, one Delhi teacher was suspended for allegedly spreading false information about the circular. Meanwhile, Mumbai teachers refused a similar “nodal officer” role, saying they’re educators, not a civic help desk.

From nodal officer to dog census: How a rumour ate the actual circular

The confusion did not stem from a complicated order; it stemmed from a story that was too neat to resist. An Instagram post claimed the Delhi government had “assigned school teachers” to assist in a city-wide count of stray dogs, framing it as an official deployment rather than an interpretation.ID@undefined Caption not available.A second Instagram reel pushed the same narrative, implying teachers were being “deployed” for stray-dog counting—an upgrade from “coordination” to “census duty” in a single swipe. The hook worked because it was instantly legible: it turned a bureaucratic phrase—nodal officer—into a headline that writes itself.ID@undefined Caption not available.But that viral framing quickly began to overwrite the administrative reality. The Delhi DoE circular (as reported) was about nominating nodal officers and sending consolidated details for stray-dog-related coordination—not about counting dogs. That is precisely what the Directorate of Education then had to swat down publicly. Delhi’s Director (Education) Veditha Reddy calls the claim “completely false, fabricated and baseless,” adding that no order, instruction, circular or policy decision asked teachers to do any such exercise. And when the rumour refused to die on its own (as rumours tend to), the department escalated: it filed a police complaint, and Delhi Police’s cyber cell began probing the circulation of the claim. Reports say the DoE even handed over a list of social media handles that amplified it.

A circular, a claim, a suspension: Delhi’s stray-dog row turned personal

A Delhi government school teacher was suspended for allegedly spreading misinformation linked to the circular on appointing nodal officers for stray dogs. Responding to the row, Education Minister Ashish Sood said teachers were free to oppose the government, protest or raise demands—calling it a democratic right—but added that no individual should spread misleading or false information. TNN has quoted him saying, “If a teacher abandons official duty, uses inappropriate language against govt in a political context and circulates incorrect information, disciplinary action is inevitable. Anyone spreading fake news will face consequences,” TNN also noted the DoE order placed the trained graduate teacher “under suspension with immediate effect.”Another media report claims that the order did not specify a reason for the suspension. Identifying the teacher as Sant Ram, posted at Sarvodaya Bal Vidyalaya (SBV), Subhash Nagar, the report said he alleged the suspension followed his refusal to serve as the school’s nodal officer for the stray dog issue.

Mumbai teachers draw the line at nodal officer duty

TNN reported that government school teachers in Mumbai refused to act as nodal officers for stray-dog control, arguing the directive effectively pushes civic management onto an already stretched teaching workforce. Teacher unions said preventing stray dogs from entering school premises is a municipal function—linked to sanitation, campus security and animal-control systems—and warned that appointing teachers as nodal officers turns educators into compliance counters for problems they neither created nor control. In letters to the chief minister, deputy chief minister and education officials, the Maharashtra Progressive Teachers’ Association (MPTA) called the move an erosion of professional dignity, with its state president Tanaji Kamble quoted by TNN saying, “Stray dog control, cleanliness and security are duties of the government. Appointing teachers as nodal officers is an affront to their dignity and professional role as educators.”The official defence, TNN noted, was essentially procedural: the education inspector said he was implementing a court order. He also sought to soften the edges by saying teachers would only be expected to coordinate with the BMC, while the civic body would enforce action. Teachers’ point is the one the system keeps pretending not to hear: “coordination” is rarely a harmless label. Once a teacher’s name is on the file, the school becomes the last stop for accountability—even when the first responsibility sits with the municipality.

What the RTE allows and where the system quietly crosses it

The Right to Education (RTE) Act tries to keep one thing simple: teachers should teach. Under Section 27, they cannot be pulled into non-school work except for three situations—decennial census, disaster relief and elections. The reason is practical, not philosophical. A school day is not infinitely expandable, and learning suffers when teachers are routinely diverted.The system crosses that line without openly admitting it, mostly by changing the label. Instead of calling it “deployment”, it becomes “coordination,” “nodal officer duty,” “monitoring,” or “just sharing details.” On paper, that sounds harmless. In real life, it means calls to make, forms to fill, meetings to attend, questions to answer and the quiet pressure of being the person whose name is on the file.That is why teachers invoke the RTE even when the issue is safety or sanitation. They are not saying those issues don’t matter. They are saying: don’t make us responsible for what we cannot control. If stray dogs, cleanliness and perimeter security are civic functions, municipal systems must own the work and the accountability. Otherwise, the classroom becomes the default place where every unresolved public problem gets parked, neatly stamped as “coordination.”