Why Shrink Bots spell trouble

AI in psychiatry is expected to deliver big – “whatever ails psychiatry, AI promises a cure” – writes Daniel Oberhaus in The Silicon Shrink, How Artificial Intelligence Made The World An Asylum. Big tech, not just startups, has been developing digital phenotypes – using AI to parse how people interact with their phones and devices to reveal clues about their mental health. AI is expected to be the ‘wonder drug’ with its access to immense data that’ll help various types of AI apps improve diagnosis, treatment and patient outcomes.

But this is flawed, argues Oberhaus whose central claim is that contemporary approaches to AI in psychiatry cannot deliver because they operate on the basis of “unreliable and invalid conceptions of mental disorder.” Little is known about ‘biological origins’ of mental disorders. We know the what and how in psychiatry, but not the why . So, Oberhaus says, how can psychiatric AI (PAI) diagnose and treat mental disorders better than doctors by analysing big data created from flawed criteria? PAI won’t improve psychiatry – it’ll just automate and amplify its existing problems on a massive scale. The book warns this’ll lead to widespread overdiagnosis, causing millions to receive medication/ therapy for conditions they may not actually have. You may well ask, but how is psychiatry ‘unreliable’?

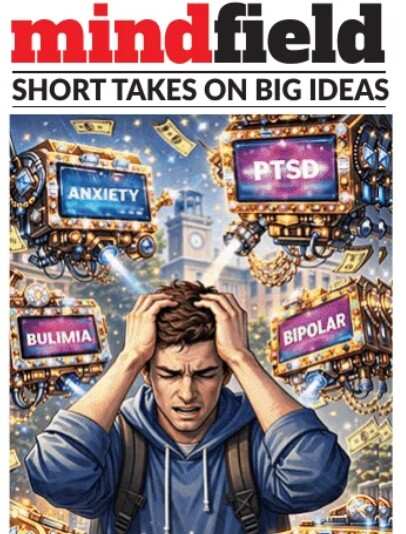

Oberhaus has dug deep, starting with his sister. The happy little girl’s behaviour changed after a schoolrelated traumatic incident. Several psychiatrists “treated” her, but nothing helped. Multiple diagnoses/ treatments later, she had asked the latest shrink: “What’s your plan for me?” Oberhaus says talking endlessly about her problems and having her down medications did not help at all. Her last sketch was a “crudely drawn person” with a stack of boxes over her head, each with a label: abandonment, eating disorders, OCD, anxiety, lack of friends, sex issues, borderline personality disorder, learning issues. Below this, she had scrawled: “No one knows what this is.”

There is still no definite definition for mental ‘dysfunction’ – just that it isn’t yet a ‘disorder’, nor a ‘disease’. What counts as dysfunction? Who decides? Dysfunction is departure from normal functioning. But what does ‘normal’ look like? The book says definitions alone show that diagnosis for conditions seen as ‘disorders’ is basis symptomatic behaviour alone. There are almost 230 different ways to be diagnosed with depression and over 6L possible symptom combinations for PTSD. So, treatment is largely subjective judgment of the psychiatrist.

Imagine now AI glugging in all the mega data around PTSD alone. Data goes in, a solution pops out. There is no step-by-step explanation to why this solution. How a maps app works out your route may not matter, but it is essential to know the why behind an AI diagnosis/ therapy.

The idea of PAI, argues Oberhaus, should be to improve patient outcomes and not pathologise all human behaviour. Psychiatry is “throwing solutions at a wall to see what would stick.” What can improvePAI is open data, explainable algos, and regulation for using AI in psychiatry. Till then, PAI will only magnify the weaknesses of current psychiatric diagnosis.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE