Top 10 best films of 2025

As the Artistic Director of the 56th International Film Festival of India (IFFI), I had the fortune of watching over a thousand films from nearly a hundred countries over the year that is now coming to an end. We eventually selected 160 of them for screening in Goa. But India is a vast country and only a fraction of our film enthusiasts can make it to Goa. In my previous roles as a film maker and cinema teacher, I have always felt that developing good audience is essential for the emergence of better cinema. And it is for this purpose that I am sharing my list of what I consider the ten best foreign films of 2025. I have not included popular English language films as they already have, as they always do, reached the viewers. My intention here is to focus on such masterpieces from far and wide that have either only been heard of and not seen, or such hidden gems that have not even been heard of. I hope the readers will seek them out, watch them and amplify conversations around them. It will be good for cinema. And it will be good for humanity.

The Columbian film A Poet, directed by Simón Mesa Soto, is a masterpiece in the best traditions of South American cinema. It is a sensitive portrayal of a simple-minded, past his prime poet, who gets into serious trouble trying to mentor a budding poetess. Eventually, he is redeemed by the same simplicity that got him into all the trouble. Soto fully captures his audience as he unfolds his moving narrative. Filming in 16 mm documentary style lends exceptional credibility to the treatment. And despite not being a professional, Ubeimar Rios’ performance as the Poet is nothing short of magical. No wonder he won the Best Actor’s award at IFFI 2025. His portrayal, along with the film’s satirical gaze at art institutions will remind many of Pyaasa and Guru Dutt, whose centenary we have been celebrating this year.

We have all seen numerous films set in Germany about the last days of Hitler. How about a film set in the same time, in the same country, but on a remote island, mostly untouched by the war except for its social and economic fallout. Based on co-writer Hark Bohm’s own childhood memories, Fatih Akin’s Amrum, takes us through the adventures of a 12-year-old Nanning whose mission is to fetch white bread, butter and honey – the only food his pregnant mother wants to eat, and the only food that is difficult to get in the island. The riveting tale explores the concepts of innocence and determination in the times of institutionalized dehumanization. DOP Karl Walter Lindenlaub’s splendid cinematography of life on the seaside makes Amrum a visual treat as well. Jasper Billerbeck’s enactment of Nanning is awesome.

If cinema is about experiencing emotions, then the Norwegian film Dreams (Sex, Love) is a great example. The film depicts the power of first love that usually overwhelms one’s entire being. And then arises the desire to share the experience, which is when the trouble begins. The film is a sensitive portrayal of honesty of feelings, the vulnerabilities of expressing them and finally the discovery of one’s the ability to move on with life. It is the last part of Dag Johan Haugerud’s trilogy that includes two earlier films – ‘Sex’ and ‘Love’. Interestingly the films have been releasing in different order in different countries. But according to the director, “in Norway, the order is ‘Sex,’ ‘Dreams,’ ‘Love.’ Love is the conclusion.” Isn’t that wonderful? The film won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival.

A liberal artist standing up to an oppressive regime makes for a fascinating fare. And the Palme d’Or at Cannes puts a seal of international approval on Jafar Panahi’s Iranian film – It Was Just an Accident. The film is a superbly structured thriller that provides a glimpse of state oppression and then goes beyond to explore if such an oppression over a long period of time can lead to widespread dehumanization of the oppressed. Oscillating between tragedy, comedy and farce – the crowning glory of the film is its culmination in hope – that despite the darkness of times, a spark of humanity can still burn bright, not only in the oppressed, but also in the oppressor.

Akinola Davies Jr’s Nigerian offering My Father’s Shadow is a shining example of contemporary African cinema. It captures one day of wonderous experiences of two young village kids Akin and Remi, as they traverse a whole new world of urban cacophony and political strife of 1993 Lagos, under the loving care of their father, who would eventually recede from their lives but remain in their consciousness as a dream. Davies narrates his tale with documentary realism by filming hand held on actual locations and keeping even the repeats and fumbles in the edit. With the gaze fixed firmly from the kid’s angle, the film succeeds in creating a strong humanist experience. And no introduction of the film can be complete without referring to the awesome acting Davies has been able to elicit from real life brothers Chibuike Egbo and Godwin Egbo playing the two kids.

Of all the films of 2025 that I saw, Omaha from America is quite disturbing. What begins as a road movie with a loving father, two playful kids and a golden retriever driving across the picturesque breadth of America, ends in a shattering heartbreak, a daring comment on consumer driven economy and an unequivocal call for reform. In terms of picking a story to film, in terms of making a feature film for the first time, in terms of filming the vast American countryside, in terms of composing evocative background music and in terms of acting by all concerned including the dog – Omaha is a triumph. No wonder Sundance chose it for the First Feature Award in US Drama category. Cole Webley is a director to look out for.

I doubt if any film featuring just two characters, talking over a cell phone for 113 minutes, has ever been made. Iranian film maker Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk brings out the Gaza tragedy more movingly than any documentary, television news story, essay or analysis that I have seen. It represents cinema’s endless ability to experiment with form and share human condition in the hope of ameliorating it. The film consists largely of a series of video calls between Sepideh and a 24-year-old woman journalist Fatma Hassona based in Gaza. The conversations filmed for a year between April of 2024 and 25, bring out the daily life of Gazans during the bombings. Sometimes they are interspersed with videos filmed by Fatma that portray a city under ruination. The cuts are almost always abrupt, reflecting the impending possibility of life getting cut without warning. At one point in the film Fatma say, “I have the idea to live here, document everything and to be able to tell my children that I have lived here and survived”. By the time of their last conversation, Sepideh has not only completed the film but it has also been selected for screening at the Cannes film festival. She conveys it to Fatma on April 15, 2025 and invites her to visit Cannes. Fatma says, “Yes, I know Cannes. I will send you my passport.” The film ends by telling us that on 16 April 2025 at 1 am, Fatma and 6 members of her family were killed in an air strike.

Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir passed away in 1919 in France, but he is very much alive in Chie Hayakawa’s 2025 Japanese masterpiece named after him. Set in mid 1980s Tokyo, Renoir takes us into the world of Fuki, an 11-year-old girl whose father is dying of cancer and whose mother is too busy looking after him to pay attention to Fuki. But the kid is far from weighed down. Level headed in tackling real life situation, she also inhabits an independent world of fantasy where she deals with truth, telepathy and even death. For those sold on cinema of visuals, Renoir makes for a delightful experience. And you marvel at the heights of excellence in story telling that this director has reached with only her second film.

Set in Saigon of 1990s, Ash Mayfair’s Skin of Youth deals with a subject that was considered taboo at that time in Vietnam, and perhaps even now. It portrays the evolving relationship between two complex characters, one a transgender sex worker seeking to realise his dream of living in a woman’s body and the other, a dog cage fighter living dangerously to support her dream. The film employs a vast visual canvas – urban shanties, nightclubs, fighting rings and sex as a refuge from harsh realities. Parallel montages work majestically to depict the simultaneous struggles of the two main characters. Skin of Youth was adjudged the Best Film of IFFI 2025.

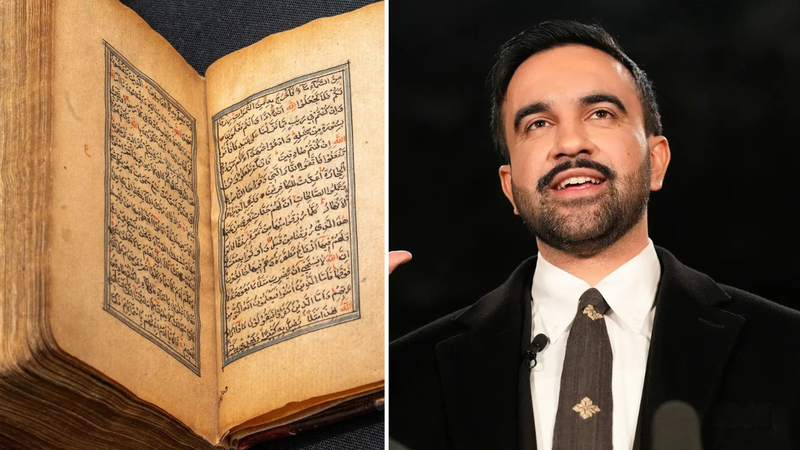

For those looking to explore contemporary Arab Cinema, Farida Baqi’s The Visual Feminist Manifesto comes as a pleasant surprise. The film takes the viewer into an unexpected, unbridled and lyrical journey of a young unnamed woman as she deals with the entrapments of social expectations and entrenched patriarchy from birth to adulthood. Structured on an evocative voice over with no actual dialogues, the visual canvas of the film spans live action, news footage, animations and old photographs. The greater part of the film, depicting scenes of social and spatial confines, are filmed in 4:3 aspect ratio. But the frame widens tellingly to 16:9 as the film reaches its conclusion with a liberating expanse of the sea. Shot on a shoestring budget with minimum crew, the film is a crowning example of inspiring work of a team comprising majorly of three women – director Farida Baqi, Cinematographer Janne Ebel and actor Amal el-Hani. The Visual Feminist Manifesto will resonate with all those facing social confinement, whichever part of the world they may be in. And it will open new frontiers for Arab Cinema.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE