Why democracies need public intelligence

“Intelligence succeeds not when leaders are informed, but when societies understand.”

President Droupadi Murmu’s address at the recent Intelligence Bureau’s Centenary Endowment Lecture was a strategic exhortation. By foregrounding people-centric national security, the address implicitly called for a shift from exclusive reliance on secret intelligence to the conscious development of public intelligence.

This call reflects a transformed security environment.

Democratisation and miniaturisation of technology have eroded the state’s monopoly on information. Capabilities that once required state treasuries now fit in civilian pockets. National security no longer confronts massed formations alone but faces millions of distributed, improvising actors operating below classical deterrence thresholds. The same technology that empowers adversaries also democratises vigilance. With doctrinal clarity and adaptive tradecraft, distributed technology can be harnessed into a resilient security mesh—blunting surprise, compressing response times, and restoring strategic balance against asymmetric threats.

For much of the twentieth century, intelligence was defined by secrecy. The advantage lay in what governments knew that others did not. This model suited an era in which wars were fought along physical frontiers, and decisions were insulated from public pressure. Today, the decisive arena of conflict is also the public mind. Secret intelligence creates a decision advantage for the executive. Public intelligence creates cognitive alignment across society.

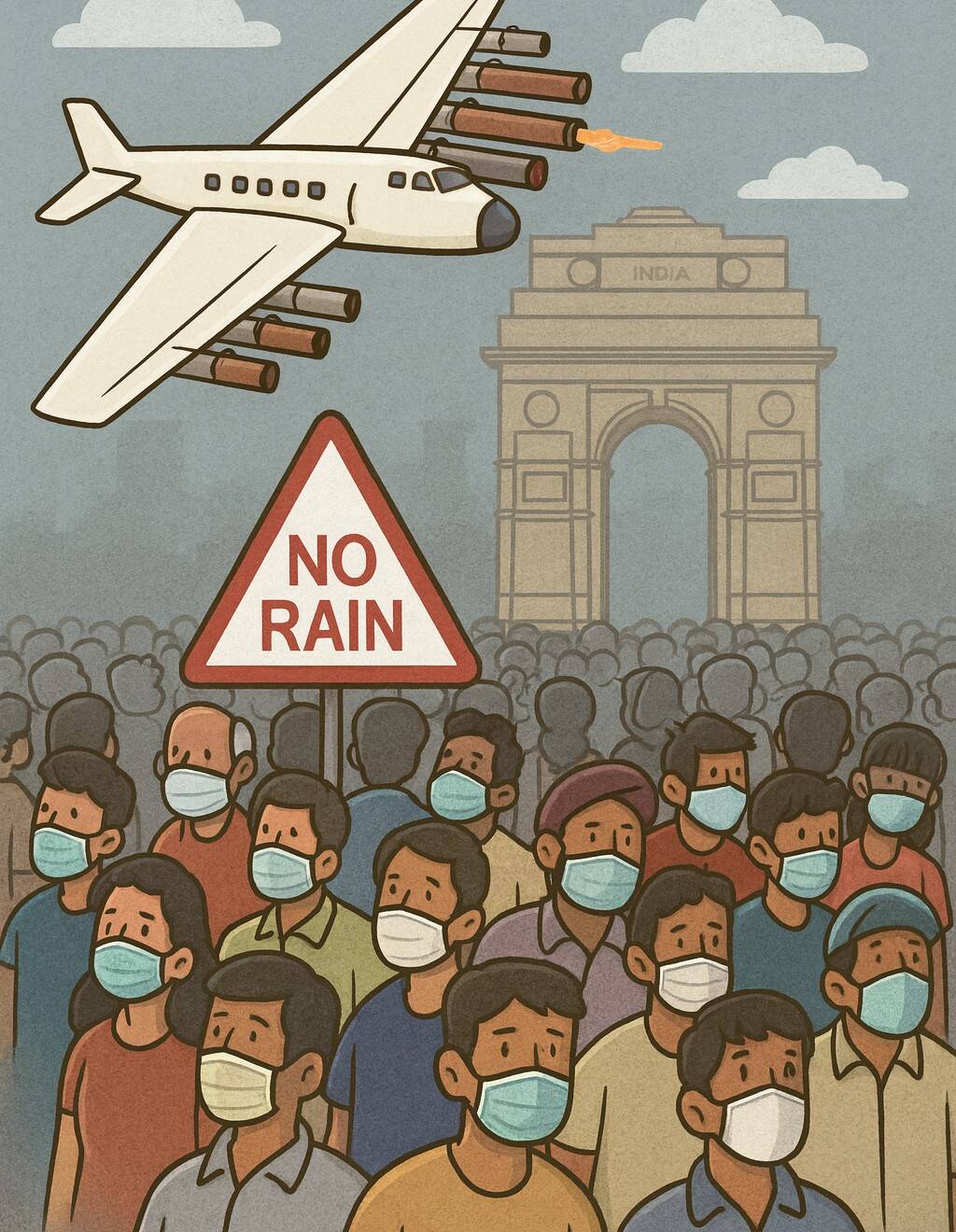

Modern threats—terrorism, disinformation, cyber coercion, grey-zone warfare—are designed to operate in plain sight. Their aim is not merely to cause damage but to sow confusion, polarisation, and erosion of trust. Against such threats, intelligence locked behind classification walls often unable to shape outcomes. Democracies, therefore, require a complementary instrument: public intelligence.

Public intelligence does not mean exposing sources or compromising operations. It means releasing carefully curated, institutionally validated assessments into the public domain to shape understanding before misinformation hardens into belief. Its function is stabilisation. Silence from the state does not preserve neutrality; it creates a vacuum—and vacuums are filled by speculation and hostile narratives.

Terrorism illustrates this clearly. An attack is rarely just an act of violence; it is a message engineered for amplification. When the state responds only with police action and classified briefings, it cedes the narrative battlefield. Fear spreads faster than facts. Timely public intelligence—attribution, context, explanation—can dampen panic and deny terrorists the psychological effects they seek.

Public intelligence also recognises a reality that intelligence organisations must acknowledge: the public is no longer merely an audience; it is a collector. Citizens generate vast quantities of information through open platforms, images, and local observation. In most contemporary crises, the first signals emerge from them. Ignoring this is institutional blindness.

The Pivot: From Warning to Control

The familiar question—Did intelligence warn us in time? belongs to an earlier era of identifiable enemies and discrete attacks. As the battlefield has shifted from borders to citizens’ cognitive space, adversaries now calibrate their actions to stay below traditional thresholds. The most significant strategic risk today is not ignorance of threats but the loss of control over the response.

This is not a failure in intelligence collection. It is a failure of doctrine.

India’s intelligence system remains primarily organised around detection and attribution. This deterrence-centric model is essential but no longer sufficient. In an environment where deterrence is eroded in small, continuous doses, the central question is no longer how to deter but how to respond without losing strategic balance.

What decision-makers increasingly require is not more information but judgment under pressure.

This is where the escalation-governor doctrine becomes indispensable. Its premise is simple yet consequential: intelligence’s most critical role is not sounding alarms but regulating response. It guides leaders on when to act, when to wait, how much force is enough, what signals to send, and—most importantly—when to stop. This is not restraint masquerading as caution. It is control by design.

Without an explicit doctrine on escalation governance, three risks persist. First, politicisation under pressure, where advice urging restraint is misread as weakness. Second, institutional drift, characterised by over-investment in collection and under-investment in impact analysis. Third, strategic inconsistency, in which each crisis is treated as exceptional rather than as part of a continuous escalation.

A formal doctrinal shift clarifies intelligence’s role as the custodian of decision space—protecting political leadership from being boxed into irreversible choices by adversary design or public emotion.

By differentiating thresholds, sequencing responses, managing attribution, and pre-structuring termination, intelligence transforms provocation into a governable problem rather than a catalytic event. In sub-threshold conflict, escalation is governed through disciplined judgment.

In democracies, escalation governance is restraint by design. It distinguishes political mobilisation from security threats, disciplines response thresholds, regulates timing, and prestructures termination. In doing so, intelligence prevents the state from amplifying the very crises it seeks to contain. The doctrine protects democratic legitimacy by ensuring that dissent is not transformed into confrontation through reflexive or symbolic overreaction.

This logic is also evident in India’s strategic challenges. China’s behaviour is not a deterrence problem but an escalation-management one. Incremental actions accumulate advantage while staying below the war threshold. Intelligence must therefore discern intent, aggregate patterns, calibrate response thresholds, and advise when restraint enhances leverage. Without this discipline, India risks oscillating between passivity and overreaction—ceding initiative either way.

Pakistan’s strategy is more explicit. Terrorism, deniability, and calibrated crises are intended to compress India’s decision space and force a reaction. Each provocation aims to accelerate public pressure and emotional demand for immediate retaliation. In such an environment, intelligence cannot stop at attribution; it must govern escalation—calibrating the timing and magnitude of the response and defining termination in advance.

Operation Sindoor demonstrated that India already practices escalation governance. Intelligence-led, threshold-disciplined, temporally controlled responses have denied adversaries control of momentum while preserving strategic choice. Practice has outpaced doctrine. It is time for doctrine to catch up.

This shift requires structural change. Intelligence organisations must develop dedicated analytical capabilities for public release, distinguishing protectable secrets from shareable judgments.

Analysts must be trained not only to assess but also to explain. Public communication cannot remain an ad hoc afterthought; it must be a standing, professionally governed function.

None of this diminishes the value of secret intelligence. Covert collection and protected sources remain indispensable. But secrecy cannot be the default response to threats that are inherently social, psychological, and informational.

The strategic error of our time is to believe that intelligence succeeds when leaders are informed, even if society is not. In democracies, legitimacy precedes resolution. Public intelligence is not transparency for its own sake; it is escalation management through cognitive means.

India’s rise ensures that threats will increase. The question is not whether India will respond, but whether it will always control the consequences of that response. An intelligence system optimised for surprise belongs to the twentieth century. An intelligence system designed to govern escalation belongs to the twenty-first.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE