Pollution prevention must replace pollute-and-clean

From cosmetic controls to individual and collective responsibility: Clean air by prevention at the source, enforcement, and public participation — not seasonal measures or pollute-and-clean gimmicks.

- Vehicles, industry, and construction dust are the main year-round pollution sources, yet responses remain short-term.

- Strong health evidence is often downplayed, exposing gaps in accountability and urgency.

- Beijing’s enforcement-led model shows that pollution can be controlled at source.

- Clean air in NCR requires prevention, long-term governance, and public participation.

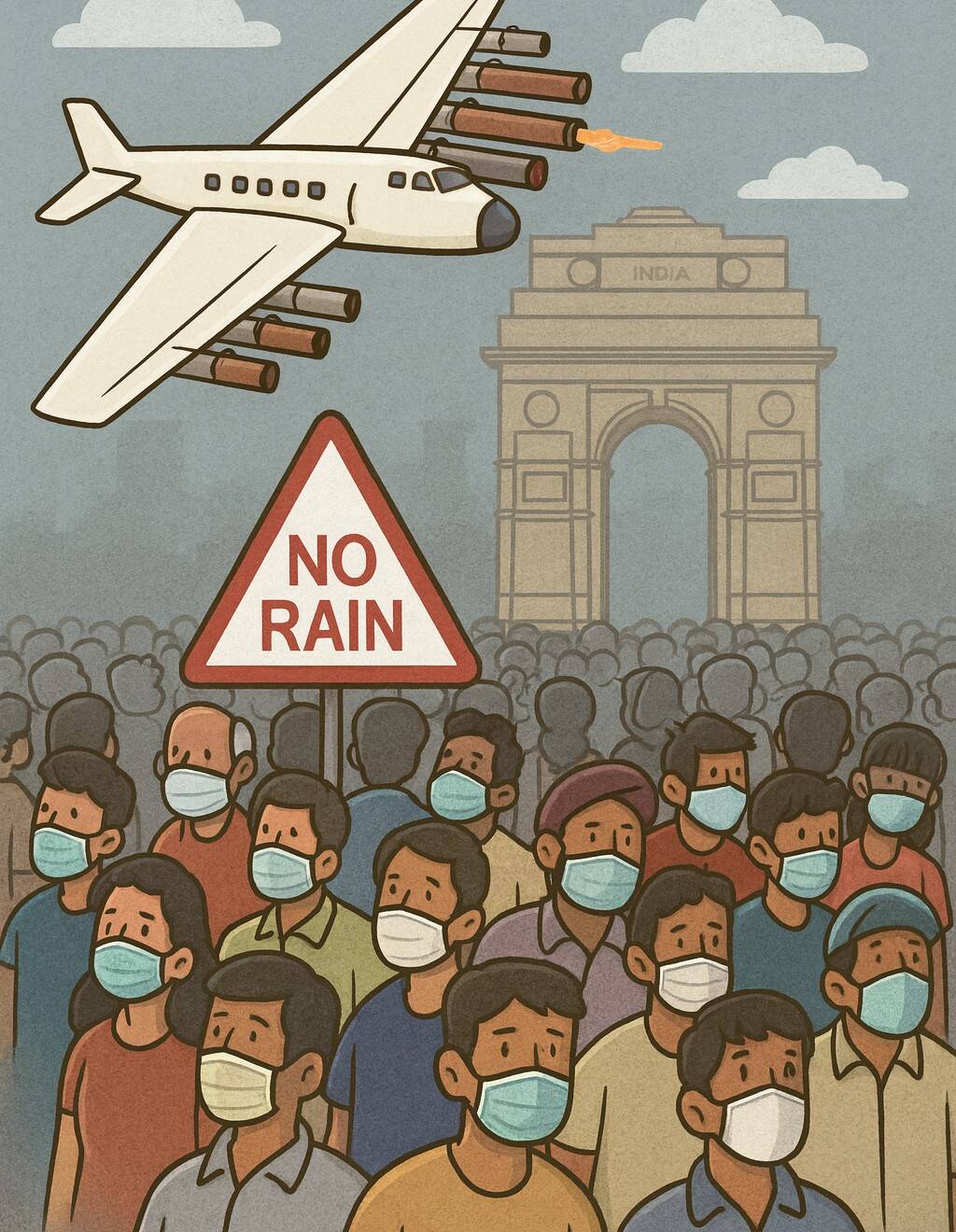

Every winter, the National Capital Region (NCR) descends into a silent public-health emergency. Falling temperatures and sluggish winds trap pollutants near the ground, blanketing the region in poisonous air. Emissions from vehicles, industry, construction dust, and biomass burning accumulate under these stagnant conditions, leaving the NCR struggling to breathe, with crop-residue burning further exacerbating the crisis. The air contains toxic gases and compounds of nitrogen, carbon, sulphate, and others, primarily from vehicular and combustion sources, which drive AQI, PM2.5, and related pollutants to dangerously high levels. Severe air pollution triggers widespread respiratory illness, hitting infants, children, the elderly, and patients with chronic lung diseases such as COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) the hardest—a pattern seen across major cities in northern India.

Governance typically responds with emergency quick fixes, such as chemical water sprinkling, episodic controls under GRAP, school closures, work-from-home advisories, and vehicle restrictions. These measures operate on a limited scale and cannot meaningfully improve air quality for a region of tens of millions. Committees are formed to issue familiar recommendations, often announced just as winter eases and atmospheric conditions improve on their own. Pollution levels fall marginally, yet remain above safe limits for most of the year, except during periods of rainfall. The cycle then repeats, year after year.

Toxic air, public health, and denial

A December 2025 assessment by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) warns that air pollution in Delhi–NCR is becoming increasingly toxic, particularly in early winter, with high levels persisting from October to November and recent gains at risk of reversal. The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) informed the Supreme Court that vehicular emissions are the largest contributor to air pollution (41%), followed by construction dust (21%), industry (19%), power plants (5%), residential sources (3%), and others (11%). Vehicular and industrial emissions together account for about 65% of the pollution load, forming the most toxic component of polluted air, dominated by fine particulates such as PM2.5 and PM1. While stubble burning and biomass are seasonal, most major sources persist year-round, sustaining hazardous air quality.

Prolonged exposure to extreme air pollution constitutes a slow-moving medical epidemic. Sustained inhalation severely damages respiratory health; when the AQI exceeds 400, even healthy individuals are affected, while vulnerable populations suffer severe and often irreversible harm. The magnitude of this crisis is well documented in the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, prepared in collaboration with the WHO. This report estimates that 1.7 million deaths in India in 2022 were attributable to PM2.5 exposure, with fossil fuel combustion accounting for the largest share.

Despite this evidence, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare stated in a written reply to the Rajya Sabha in early December 2025 that no deaths were reported due to air pollution, citing the lack of conclusive data linking deaths exclusively to air pollution. The reply emphasised that multiple factors influenced, including diet, occupation, socioeconomic status, medical history, immunity, heredity, and environmental conditions. An identical response was submitted earlier to the Lok Sabha in July 2024 by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) in July 2024, and again in mid-December 2025.

Repeated, identical replies from two key ministries reflect a troubling lack of seriousness and accountability in addressing a well-established health crisis. This persistent apathy underscores the urgent need to recognise air pollution as a public-health emergency — a slow but deadly threat, particularly for infants, the elderly, and those with chronic respiratory illnesses. Meanwhile, governance continues to rely on gimmicks and short-term fixes rather than tackling the root causes.

Lessons from Beijing: Enforcement over gimmicks

Not long ago, Beijing faced pollution levels comparable to those now seen in the NCR. Its turnaround did not come from seasonal fixes or symbolic measures, but from firm, sustained, and enforceable action. Through decisive governance, Beijing delivered visibly cleaner air. India does not need to reinvent solutions; it can learn from Beijing’s experience.

Beijing’s success rested on a multi-pronged strategy that tackled pollution at its source, especially emissions from vehicles and industry. Measures included ultra-stringent emission standards, the phased removal of older high-emission vehicles, limits on the unchecked growth of private car use, substantial investments in clean mobility through metro systems, buses, rail, and electric vehicles, and the relocation of polluting industries away from densely populated urban centres. These hard choices, backed by consistent enforcement, produced measurable and lasting improvements in air quality.

Drawing from these lessons, Indian governance must move beyond populist gimmicks and short-term fixes. The public — the most affected stakeholder — deserves honest communication about the severity of the crisis and an explicit acknowledgement that quick solutions do not work. Addressing air pollution requires tough, evidence-based decisions, long-term planning, and the political will to prioritise public health over convenience.

People-led change for sustainable solutions

Lasting solutions demand a long-term strategic plan, substantial investment, and sustained public acceptance and cooperation at every level. History shows that many meaningful environmental reforms have been driven not by short-term government fixes, but by an awakened and engaged public. A notable example is the Chipko Movement, which opposed deforestation linked to the construction of the Tehri Dam, led by Sunderlal Bahuguna. Through non-violent resistance and mass mobilisation, the movement drew national attention to the ecological and social costs of large infrastructure projects, reinforcing the principle that development must be guided by sustainability, scientific understanding, and public participation.

In parallel, a sustained civil movement is essential to complement policy action through individual and collective responsibility. Citizens can reduce emissions by lowering their dependence on private vehicles and shifting to cleaner modes of transport, such as metros, buses, rail, shared mobility, and electric vehicles, wherever possible. Communities can actively promote tree plantation and protect existing green cover to improve local air quality. At the neighbourhood level, cooperation is vital to curb other emission sources — including construction dust, waste burning, and the use of diesel generators — through shared vigilance and mutual consent. Such visible, citizen-led action can generate public momentum and provide governance with both the confidence and the social mandate to implement tougher, but necessary, measures.

The way forward

The path forward lies only in long-term solutions that reject the cycle of polluting first and attempting to clean up later. Preventing pollution at the source — or not polluting at all — is the only viable alternative. It requires expanding pollution-free infrastructure, enforcing strict emission standards, and taking hard but necessary steps such as relocating polluting industrial units away from densely populated areas. These measures are complex and demanding, but they offer the only credible route to sustained improvement in air quality.

To achieve this, governance must move beyond advisory committees and constitute task-oriented bodies empowered to assess feasibility, estimate costs, set clear timelines, and drive execution. What is required now is action on a war footing, grounded in science & technology, accountability, and shared responsibility across institutions, industry, and society. Only such decisive, coordinated implementation can break the cycle of recurring crises and deliver breathable air as a public good.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE