The end of volume or velocity journalism has been announced before. It never quite arrived.

I spent these December weekends doing what digital editors now perhaps do on long weekends – watching lines fall.

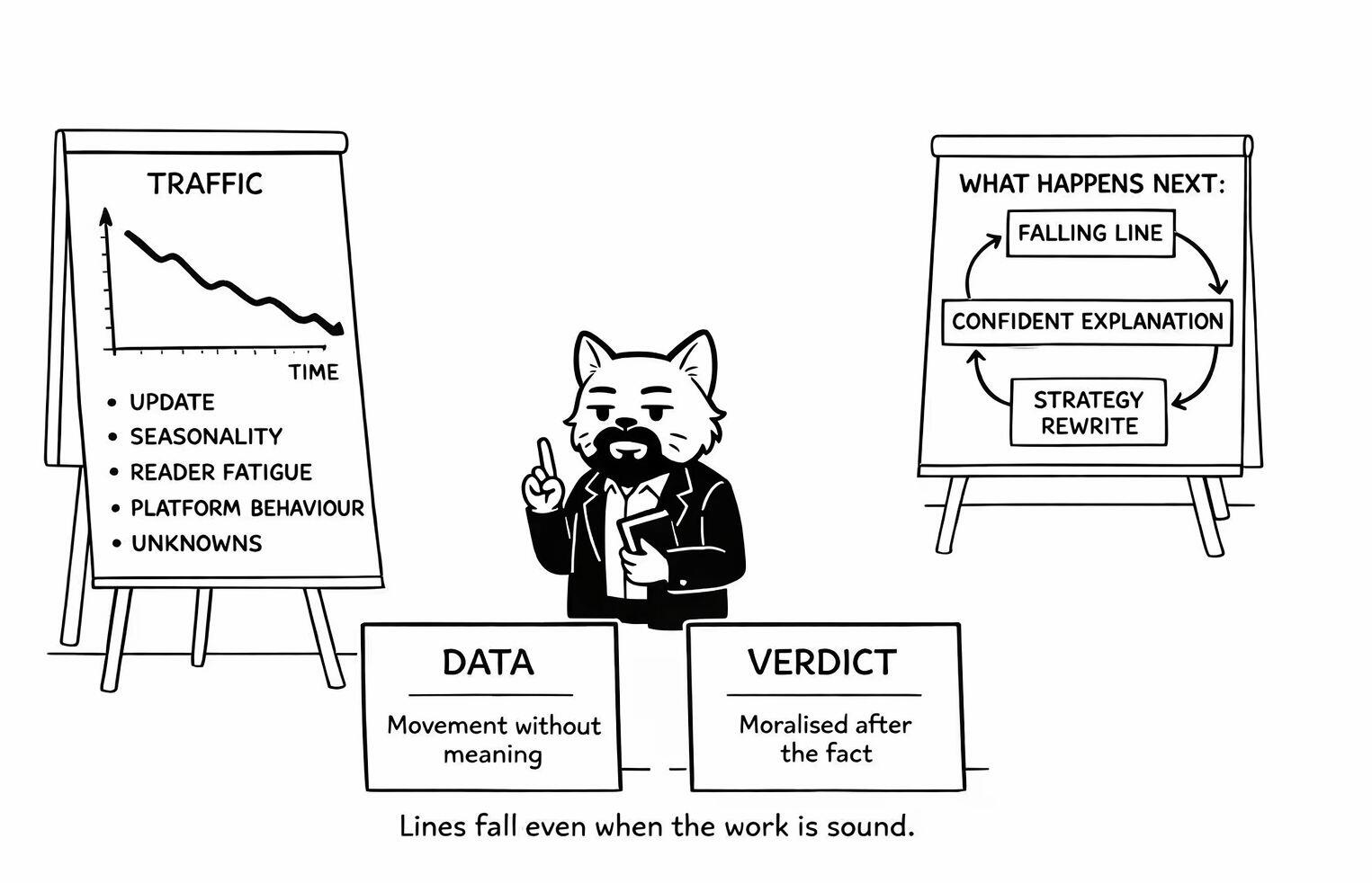

Traffic charts, update notes, before-and-after comparisons, the familiar ritual of trying to locate meaning in a graph that refuses to explain itself. Somewhere between the third dashboard refresh and the fourth theory, Sahir Ludhianvi drifted in uninvited, as he often does when certainty begins to wobble. ‘Khwaab ho, tum ya koi haqeeqat’ Are we looking at a dream, or at something real?

Every algorithmic update arrives with its own sermons. This one speaks in the language of meaning. Not keywords, not brute scale, not the velocity with which newsrooms push stories into the world, but something more elevated: semantic depth. The machine, we are told, now understands ideas, nuance and context. And from this understanding flows a familiar promise, delivered with great confidence. Volume or velocity journalism will finally be punished. Fewer stories, deeper thinking, harder-to-summarise work will be rewarded.

It is an attractive idea, especially when you have just watched traffic dip for reasons no one can fully explain. It flatters editors who have always believed that the problem was never journalism, only distribution. It reassures long-form writers who have survived one too many conversations about output and efficiency. It offers the hope that the dashboards might one day align with our better instincts.

But hope, as Sahir reminded us in a different age, has a habit of disguising itself as truth. Before we reorganise our newsrooms around the latest interpretation of machine intent, it is worth separating three things that are too often spoken of as one: algorithmic capability, media economics, and newsroom strategy. They influence each other, certainly. They do not, however, move in step. They never have.

There is no question that algorithms today are more capable than they were even a few years ago. They no longer treat journalism as a sack of keywords to be matched and discarded. They recognise ideas as relationships, topics as clusters, context as something closer to structure than coincidence. This allows machines to retrieve, group, and summarise information with a level of sophistication that would once have seemed improbable. But this is also where the technical story is frequently asked to do too much cultural work.

Understanding what a piece of journalism is about is not the same as caring how it was produced, why it matters, or whether it deserves to travel further than the rest. Retrieval is only the first act in a much longer play. Ranking, distribution, and monetisation are shaped by incentives that remain resolutely commercial. Machines optimise for goals. Goals are set by institutions. Institutions, as history keeps reminding us, are rarely in the business of moral alignment.

At this point, some platforms and observers speak with such certainty about what will now be ‘rewarded’ that one is tempted to ask, gently and with admiration, what exactly they are seeing that the rest of us are not. There is a confidence here that feels almost recreational. I do not want to smoke what they’re smoking exactly, but I would very much like to know the strain.

There is another misunderstanding that quietly slips into these conversations, particularly when newsroom thinking borrows too eagerly from engineering language. The belief that information density is an unqualified good.

Density is an engineering instinct. It values compression, efficiency, and maximum signal per unit of space. For machines, this makes sense. For journalism, it is often corrosive. An obsession with density encourages the stripping away of context in the name of usefulness. It rewards writing that sounds complete while discarding the scaffolding that allows readers to understand why something matters, where it came from, and how it connects to what they already know. The result is content that is technically accurate, briskly consumed, and almost immediately forgotten.

Journalism does not exist to move the greatest number of facts in the shortest possible time. It exists to make sense of the world as people experience it, which is rarely linear and almost never dense. Meaning emerges not from compression but from placement. From what is included, what is explained, and what is allowed to breathe. Context, in this sense, is king. Context requires memory, not just data. It requires judgement, not just relevance scoring. It asks editors to decide which facts belong in the foreground, which require framing, and which only make sense when seen alongside their consequences. When density becomes the goal, journalism begins to read like documentation. When context leads, it reads like understanding.

This is also why the belief that smarter machines will naturally privilege better journalism often misfires. Machines are becoming better at recognising what is being said. They remain largely indifferent to why it is being said, or to whether the reader is encountering it for the first time or the fiftieth. That responsibility has not been automated away.

This misunderstanding becomes even clearer when we look at how people actually consume news. News consumption today is driven not by a single desire to stay informed, but by a shifting mix of emotional, practical, and intellectual needs. People do not just want to know what is happening. They are trying to understand why it matters, how it affects their own lives, and what, if anything, they should do about it. On some days, they seek clarity and explanation. On others, reassurance or orientation in a world that feels slightly more unsteady than it did the day before. There are also moments when the need is lighter and no less legitimate. A reader may be looking for a story that offers relief, perspective, or even a small measure of amusement in the middle of a crowded day.

Journalism, at its best, has always met people where they are, not where a system assumes they should be. Depth, in this context, is not an abstract virtue. It is situational. It appears when the reader is ready for it, not when an algorithm decides to surface it. That is why depth has always been chosen deliberately rather than encountered accidentally. It builds trust and loyalty over time, not scale in the moment. Algorithms may become better at identifying complexity, but they do not experience fatigue, anxiety, curiosity, or boredom. They do not know when a reader wants instruction, when they want interpretation, and when they simply want a few minutes of uncomplicated relief. Identification is not empathy. And empathy, inconveniently, remains central to journalism.

This is where the moral framing of volume or velocity journalism begins to wobble. Speed has always been intrinsic to news. Scale has always been part of its social function. The real distinction was never between fast and slow, or between many stories and few, but between work produced with intent and work produced on autopilot. Between coverage that understands its audience and output that merely satisfies a system. There is repetition born of laziness, and there is frequency born of presence. Some of the most valuable journalism has been produced at pace, by reporters and editors who knew their terrain well enough to move quickly without becoming incoherent. Conversely, some of the most indulgent long-form work has offered little beyond the performance of seriousness. The failure, when it occurs, is not velocity. It is thoughtlessness.

There is a deeper risk in allowing newsroom strategy to be written as a footnote to algorithmic change. It trains organisations to wait for signals rather than set direction, to treat every update as instruction. Over time, judgement is replaced by pattern recognition, and leadership by optimisation. Strong editorial strategy does not begin with machines. It begins with audience understanding, institutional memory, and a clear sense of purpose. With knowing what you are uniquely equipped to cover, and what you can safely ignore. Technology can amplify that clarity. It cannot manufacture it. Chasing what the system appears to reward at any given moment is a reliable way to always arrive slightly too late, optimised for a version of the world that has already moved on.

Perhaps this is why it feels like the right note to end the year on. A moment to look back at the lines we have chased, the stories we have shipped, the convictions we have defended, and ask—quietly—what was signal, what was noise, and what we want to carry forward when the screens light up again in January.

Every generation of journalists want to believe that the next technological turn will finally align virtue with reward. That good work will rise naturally, shallow work will sink, and the lines on the screen will begin to make moral sense. They rarely do. Technology will continue to reshape the tools. Economics will continue to redraw the boundaries. Strategy will remain a human responsibility, exercised under pressure, with imperfect information, often after the numbers have already moved.

Somewhere in all this, the newsroom still has to decide who it wants to be when the charts dip and the explanations thin out. Whether it responds by chasing the next pattern, or by returning to first principles. Whether it treats every falling line as a verdict, or merely as data. Lines fall all the time. They fall after updates, after redesigns, after decisions that felt right when they were made. They fall even when the work is sound. And sometimes they rise for reasons that have nothing to do with merit. The mistake is not in watching them. It is in mistaking them for self-evident truth.

What endures, unfashionably and without dashboards to prove it, is judgement about what deserves attention, what can be done well at speed and what demands time; about when to publish, when to hold, and when to ignore the noise entirely. The newsroom that survives is not the one that guesses the machine’s mood most accurately, but the one that can look at a falling line and still recognise itself in the work. When the screen goes dark, and the weekend ends, that recognition matters far more than the direction of the graph.

Further Reading

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE